Let’s say you have the next great technological innovation that is ideally suited to thrive in both commercial and public sectors. Who do you call and where do you go? In the private sector, you may go to the patent office to file for a new design, reach out to potential manufacturers, or consider reaching out to larger corporations who may be interested in licensing or purchasing the product. Well, in the public sector, it’s not that easy. You have to go through the front doors of the government, which are incredibly hard to find.

Perhaps this is not surprising given the opaqueness of government institutions. This fact, the ambiguousness with which the public at large interacts with the government, is one with which public officials have grappled for years. In fact, in 2016 the federal government widely acknowledged this challenge when it launched the initiative “Federal Front Door,” designed to increase citizen’s satisfaction with their interactions with the government.69 The goal is to improve user experience by improving transparency in a service, promoting information sharing among agencies, and eliminating redundancies of interactions with the government.

Having a front door is critical to the success of creating products and services for the government. “If you really want to understand what the government’s problem is and see if you have a potential solution, you need to have people who can walk through the door and listen. And that doesn’t mean just anyone, it has to be someone who can speak the government’s language. Having these doors into government means a better understanding in the commercial sector to what the problems are,” says Niloofar Razi Howe, a fellow in New America’s International Security Program and an investor, executive, and entrepreneur in the technology industry for the past twenty-five years, with a focus on cybersecurity. Razi Howe goes on to say, “The front doors of government also provide…for people in the private sector, with that important sense of mission, an opportunity to approach and work with the government. Without it, it’s easy to get lost in the weeds of the government, figuring out who to work with, what the processes are, and how to best position your company.

“You want organizations that are genuinely trying to go out and partner with technology companies and come in and create a testing ground for the best solutions to be able to pull them in, understanding that they’ve been a super hard agency to work with,” Razi Howe says. “In many cases where we have seen a clunky procurement process, some of these front doors have seriously benefited our nation. I have seen cases where there’s a great commercial technology that the U.S. government should be procuring but the request for proposal process makes it impossible to do that. The process is too long and painful for the manufacturer. So, they end up going with a larger vendor who makes a custom-built version of the technology. The front doors can help in getting the right technology into the hands of the government.”

Front doors are also for people. “People are skeptical of the government. This is really no surprise for anyone who has turned on the news lately,” says Jason Matheny. He adds, “And they should be. Governments can do terrible things. But what is the best way to stop these things? By joining the government. There’s no better way to ultimately reduce the harm and increase the benefits of government than by joining the government.” But according to Matheny, government is not any different from most organizations, as it also hopes to attract talent with integrity. He goes on to say, “There is no perfect organization on the planet. Every major company that you can think of likely has at least one moral objection to what they are doing. The simple fact is that there are dangerous activities everywhere, but you need safety breaks in these organizations to reduce this harm. The best way to improve government is to just walk in the front door and start fixing things.”

In August 2021, the Biden administration helped create one such front door for people looking to join the government’s mission, the U.S. Digital Corps. This collaboration between the General Services Administration, Office of Personnel Management, the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency, and the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy created a cross-government fellowship that sought to bring entry-level technologists into the government. As referenced in Chapter 1, the federal government has a clear technologist deficit, which the U.S. Digital Corps is aiming to fill. The U.S. Digital Corps is a paid, full-time, two-year fellowship that has the opportunity to convert into a full-time career position after successful completion of the program.70

Chris Kuang, a cofounder of the U.S. Digital Corps, recalls the inspiration for this initiative. “When I was a college student, I remember searching USAJOBS for an entry-level position that combined two of my passions: technology and public service. Imagine how I felt when the only result that came back was an unpaid position installing basic software! That experience set me on a path of creating more opportunities for students and recent graduates in public interest technology, which is why I am so excited that we were able to launch the U.S. Digital Corps.”71 Creating the U.S. Digital Corps was a natural extension of Chris’s prior work as a cofounder of Coding it Forward, a nonprofit by and for students creating opportunities and pathways into social impact and civic tech. “Cofounding and helping lead Coding it Forward while engaging with so many passionate students and young people from across the country—and around the world—was an incredible privilege and opportunity. At its roots, I have always seen Coding it Forward’s work as aspirational. Our work as an organization and a broader civic tech movement will have won a victory when using tech, data, and design skills in service of the public interest is considered the gold standard—the “dream job”—and perhaps even an expectation. But our work will not be done until there are enough opportunities inside and outside of government to meet and truly take advantage of this growing supply of mission-driven talent.” Chris’s work in the U.S. Digital Corps and Coding it Forward show his commitment to making more front doors for those seeking to work for the government.

Government initiatives to create more front doors are critical to creating trust in government. For ventures, this means the government is giving a better understanding of where to identify opportunities for products and services. For individuals, this means the government is providing an opportunity to better understand where they can look for impactful and mission-driven work. But while the government initiatives to create front doors are valiant efforts to overcome the difficulty of working with the government as a purchaser or consumer of venture and citizens’ goods and services, the idea of too many front doors is quite concerning. For example, the recent focus on innovation to foster creative problem solving in the U.S. government has produced a number of exceptional programs meant to foster partnerships with the private sector, including Challenge.gov (a platform for prize competitions in federal agencies), CitizenScience.gov (a resource designed to accelerate the use of crowdsourcing and citizen science across the government), and NASA Solve prize competitions and crowdsourcing.

But sorting through these initiatives and identifying which are the most appropriate for specific products and services can be daunting, hence, the challenge of “too many doors.” “Look no farther than the Department of Defense,” says Trae Stephens, a partner at Founders Fund, who invests across sectors with a particular interest in startups operating in the government space. “There are over a hundred different innovation organizations and software factories inside the Department of Defense. Over a hundred! It’s impossible for an outsider to know where to start.”

While the government maintains a key role in the Venture Meets Mission ecosystem, we would be remiss to overlook the critical role of social enterprises in aiding impact. We take a more expansive view of social enterprises as existing in many forms, as foundations, triple-bottom-line firms, and nonprofits. These organizations help testbed ideas and new business models that can be scaled by government, provide risk capital through foundations to develop mission enterprise, and serve as an intersectional convener that can bridge trust across government, the private sector, and academia. Simply put, nonprofits are an ecosystem catalyst.

The president and CEO of the World Wildlife Foundation, Carter Roberts, acknowledges this, stating, “People look to WWF and its leadership to bring imagination and perseverance to the important work of conservation, and to build bridges between government, civil society and business in devising solutions at the scale of the challenges we face. The world demands no less of us.”72 As we look to other nonprofits, we see the role of these organizations in driving change around mission-driven work.

The recent work of Dr. Eric Schmidt, the former CEO of Google who recently announced the launch of the Special Competitive Studies Project (SCSP), is one example of a social enterprise aiding the government’s impact and facilitating the government’s mission. This initiative will make recommendations to strengthen America’s long-term global competitiveness for a future in which artificial intelligence and other emerging technologies would reshape national security, economy, and society.73 It is quite similar to the Rockefeller Special Studies Project launched in 1956 by Nelson Rockefeller. In the midst of the Cold War, Rockefeller brought together some of the nation’s leading thinkers to study the major problems and opportunities confronting the country to chart a path to revitalize American society.74

Interestingly, Schmidt’s decision to form the SCSP comes from a feeling of empowerment to support the mission of government. “Federal government support launched my career,” says Schmidt. He elaborates, “My graduate work in computer science in the 1970s and 1980s was funded in part by the National Science Foundation and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency. Five years ago, I was fortunate to be able to start giving back when then-Secretary of Defense Ash Carter asked me to serve on the Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Board, and then three years ago, Congress asked me to chair the National Security Commission on Artificial Intelligence. Both of these roles convinced me that the U.S. needs to think, organize and compete in significantly new ways. No serious nation can ignore the impacts of emerging technologies on all aspects of our national life. Our government cannot be a passive actor, but it needs help. For this reason, I am starting the Special Competitive Studies Project…to study these critical issues alongside my friends and colleagues.”75 And the SCSP is successfully aiding the government in identifying and coordinating new tech for long-term global competitiveness, as seen most recently in a new project on human-machine teaming in military operations.76

Another organization helping to enable impact is youth-led social enterprise unBox, cofounded by Isa Foster and Charlie Hoffs. This organization is working to empower younger generations to fight food insecurity, by connecting these individuals with “the tools, training, and networks needed to transform US food policy through research, policy advocacy, and activism.”77 Recently, unBox collaborated with the government on addressing nutrition and food security issues in legislation. Working with Senator Richard Durbin on legislation S. 4202, “Expanding SNAP Options Act of 2020,” unBox was invited to review the legislation as it was being drafted and offer suggestions on what should be included to overcome existing policy barriers. By bringing together research, subject matter experts, and other organizations, unBox was able to help the government understand the true nature of the problem in their drafting of legislation, enabling better impact.

All Tech Is Human is another organization helping orchestrate the government’s mission. This nonprofit group maintains that the future of technology is intertwined with the future of democracy, and that a “responsible technology ecosystem” is critical to a functioning democracy.78 This group, as many scholarly works have underscored, argues that an entanglement of technology with social, political, and economic systems that are inherently unjust means that advances in technology are hindered from being a public and planetary good. All Tech Is Human is seeking to instill the ideals of a liberal democracy in new technologies through multistakeholder convening, intersectional education, and diversifying the pipeline of talent with more backgrounds and experiences.79 By working with the government to ensure that technological trajectories and development are aligned with the public interest, All Tech Is Human is helping the government orchestrate its mission. Such social enterprises also provide a chance for new models of engagement to be tested, and later scaled with government assistance.

And while the government is struggling to attract talent to the ecosystem, we are seeing examples of how nonprofits can help develop talent. Teach for America, a nonprofit organization whose stated mission is to “enlist, develop, and mobilize as many as possible of our nation’s most promising future leaders to grow and strengthen the movement for educational equity and excellence,”80 is a great initiative that has produced exceptional public servants, successful entrepreneurs, and business leaders. Activate Global is a nonprofit that partners with research institutions and U.S.-based funding organizations to support fellows in an “entrepreneurial fellowship model.” The organization sits between the government and the private sector to help transform scientists into entrepreneurs through a fellowship that guides them through the journey. Their 142 fellows have generated $1.3 billion in follow-on funding and created over twelve hundred jobs.81 And MissionLink.Next is a nonprofit trade association that is helping to train CEOs on opportunities to leverage their company’s technologies to address emerging mission-critical opportunities.82 These are recognizable models that have been able to draw an array of talent from different backgrounds and interests, and cross-fertilize the public sector with private-sector talent. Thus a solution to attracting talent into the Venture Meets Mission ecosystem may be through nonprofit organizations that sit outside of government and promote public service.

And finally, social enterprises are helping to mobilize capital around the government’s mission. The Elemental Excelerator, a not-for-profit platform of the Emerson Collective, is committed to mobilizing capital around mission-driven work. They hold a portfolio of for-profit companies in energy, sustainability, water, agriculture, transportation, finance, and cybersecurity. Since 2009, the nonprofit platform has invested in over 150 companies, celebrated over twenty-five exits, and funded more than a hundred technology projects.83 Among their accomplishments was the significant impact they made to these ventures, with their portfolio leveraging Elemental’s dollars 100x and raising over $3.8 billion in follow-on funding.84 Even more impressive is the origin story of the organization, which brought together renewable energy and military capability in the form of a $30 million award from the DoD’s Office of Naval Research to scale their program impact and support the navy’s climate initiatives. The Gates Foundation is an example of philanthropy for mission-driven ventures and innovations. Created by Bill and Melinda Gates, this nearly $50 billion endowment provides funding to organizations in order to achieve measurable impacts in the fight against poverty, disease, and inequity around the world.85 This base of philanthropic capital mobilizing around mission-driven ventures certainly aids in providing critical funding to the ecosystem, as these social enterprises risk capital to develop the mission enterprise. In the Venture Meets Mission ecosystem, nonprofit organizations play a key role in catalyzing the ability for governments and ventures to scale their impact.

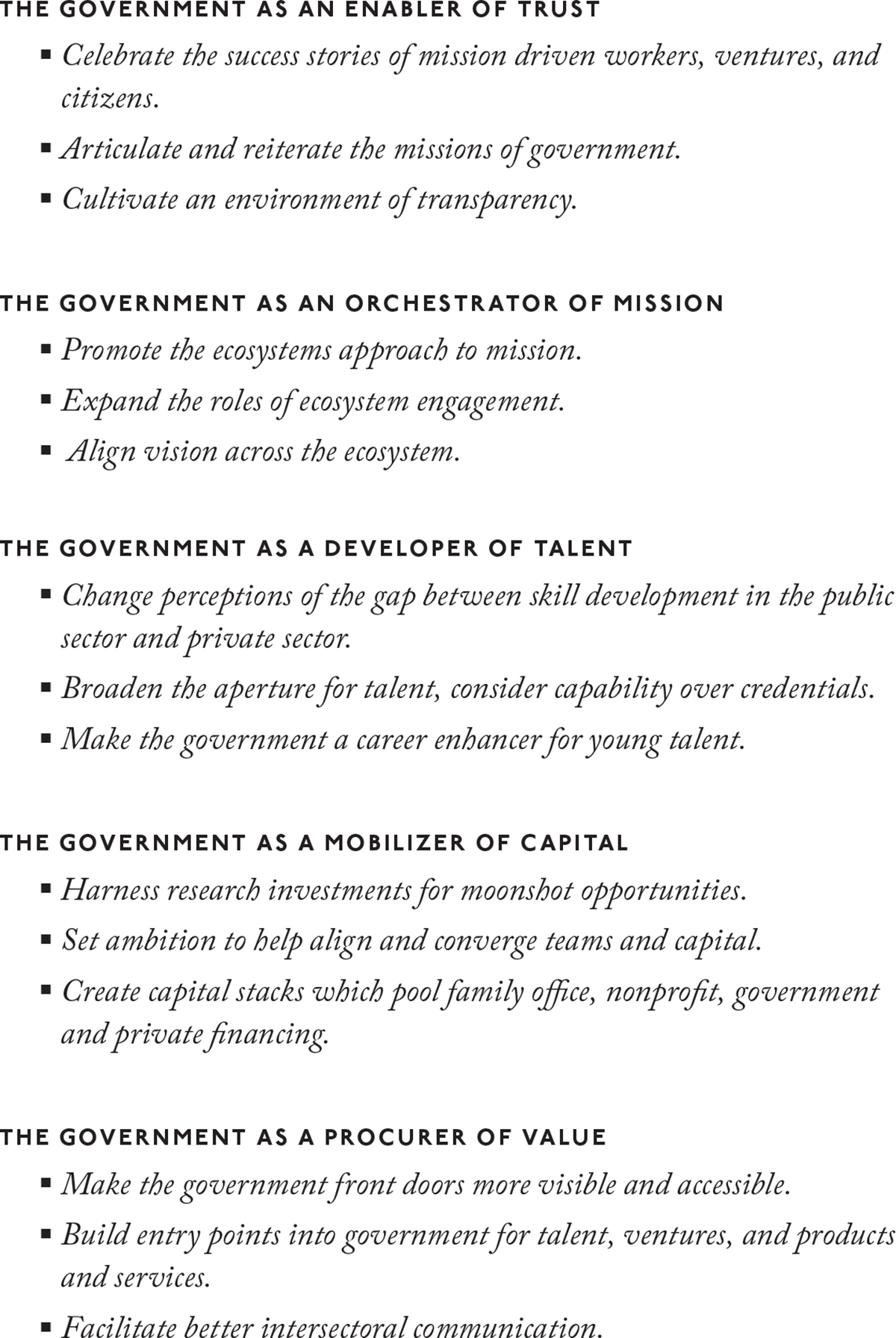

We summarize the key roles of government as an enabler of trust, orchestrator of mission, developer of talent, mobilizer of capital, and procurer of value (Figure 5.1). To rebuild trust, governments need to assume their role as an enabler by continuing to act with a commitment to the public interest in a transparent manner. By articulating mission and celebrating success stories, governments can be an enabler of impact. To orchestrate collaboration, governments can adopt an ecosystems approach to mission—rallying people around societal problems, expanding the roles of engagement, and aligning ecosystem vision with key participants. As a developer of talent, the government can reduce perceptions of incompatible skills in the public and private sectors, broaden their talent search, and make the government a career enhancer for young talent. The government can also play a key role in the mobilization of capital around mission through various agency initiatives and wealth funds, creating capital stacks that leverage government spending and reduce the financial risks of government investments. The government can enhance its role as a procurer of public value by making it easier to work with and for the government in support of its larger mission and to cultivate an outcome-focused marketplace. Finally, social enterprises are critical in the Venture Meets Mission ecosystem, by serving as testbeds for new models, finding new sources of funding, and convening participants across sectors to rebuild trust.

69. “The Public’s Front Door to Government Services,” U.S. Government Services Administration, accessed August 13, 2022, https://labs.usa.gov/.

70. “The Opportunity: Begin Your Career at the Intersection of Technology and Public Service,” United States Digital Corps, accessed August 13, 2022, https://digitalcorps.gsa.gov/opportunity/.

71. Chris Kuang, “Introducing the U.S. Digital Corps: A New Path to Public Service for Early-Career Technologists,” ChrisKuang.com, September 2021, https://www.chriskuang.com/words.

72. “Leadership,” World Wildlife Foundation, accessed December 14, 2022, https://www.worldwildlife.org/about/leadership.

73. Frank Wolfe, “Eric Schmidt to Helm National Artificial Intelligence/Emerging Technologies Project,” Defense Daily, October 5, 2021, https://www.defensedaily.com/eric-schmidt-to-helm-national-artificial-intelligence-emerging-technologies-project/advanced-transformational-technology/.

74. “In Depth: The Special Studies Project,” Rockefeller Brothers Fund, accessed December 14, 2022, https://www.rbf.org/about/our-history/timeline/special-studies-project/in-depth.

75. “Dr. Eric Schmidt Announces Special Competitive Studies Project,” AIthority, October 5, 2021, https://aithority.com/security/dr-eric-schmidt-announces-special-competitive-studies-project.

76. “SCSP and RUSI Launch a New Project on Human-Machine Collaboration and Teaming in Military Operations,” Special Competitive Studies Project, November 10, 2022, https://www.scsp.ai/2022/11/scsp-and-rusi-launch-a-new-project-on-human-machine-collaboration-and-teaming-in-military-operations/.

77. “Who We Are,” UnBox, accessed December 2, 2022, https://www.unboxproject.org/.

78. “Who We Are,” All Tech Is Human, accessed November 29, 2022, https://alltechishuman.org/about#purpose.

79. “Responsible Tech Guide: How to Get Involved & Build a Better Tech Future,” All Tech Is Human, September 2022, https://alltechishuman.org/responsible-tech-guide.

80. “What We Do,” Teach for America, accessed August 17, 2022, https://www.teachforamerica.org/.

81. “From Zero to One,” Activate Global, accessed March 8, 2023, https://www.activate.org/impact.

82. “About MissionLink.Next,” MissionLinkNext, accessed March 17, 2023, https://missionlinknext.com.

83. “How We Work,” Elemental Excelerator, December 15, 2022, https://elementalexcelerator.com/.

84. “Scaling Climate x Social Equity Solutions, 5 Year Strategy,” Elemental Excelerator, April 2021, accessed December 8, 2022, https://elementalex-celerator.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Elemental-5Y-Strategy-Scaling-Climate-x-Social-Equity-Solutions.pdf.

85. “How We Work,” Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, accessed November 29, 2022, https://www.gatesfoundation.org/about/how-we-work.